Thursday, January 13, 2011

Things on Thursday: Books I've Read

I liked all of these to varying degrees, though I admit that When and How to Use Mental Health Resources (a textbook for Stephen Ministers) was hard slogging.

What did you read in the last 12 months that stuck with you? What are you reading now?

I'm considering becoming more active on the website Goodreads. I think it will be a fun way to help me live out my Word of the Year: Learn. Do any of you use it? Care to share your thoughts?

Wednesday, September 15, 2010

Book List

Or, if you're a masochist, you can use the snootier book lists to feel really bad about yourself for not even recognizing four-fifths of the titles on them. I don't really recommend that, though.

Most of the lists that came out in 2000 focused only on the twentieth century, and we've already established in this essay that the twentieth century didn't produce my favorite works of literature. My favorites are mostly really really old and were written when the word eek meant also, not yikes, a spider!

Eek, I am geek.

Anyway, I came across the following list on FaceBook and liked it a lot...and not just because I've read so many of the books on it, though I confess that is part of the reason. Mainly, this list appeals to me because it has lots of different sorts of novels from earlier times and also children's novels. It's not a snooty list at all. It includes The Adventures of Winnie the Pooh, for heaven's sake. I also really like the fact that James Joyce isn't number one or number two on it. His novel Ulysses is number 78.

For the record, I have read Ulysses and thoroughly enjoyed it. It truly is a great novel, perhaps the best ever written. It is, however, an acquired taste, a bit like red wine. If you're used to drinking light, crisp, chilled pinot grigio and someone hands you a glass of room-temperature cabernet, your taste buds will balk at the complexity and big, fruity chewiness of the wine. That describes a first encounter with Ulysses, too. The complexity and mental chewiness of it are revolutionary, and you need to have acclimated your brain to that sort of thing before drinking its full glass with pleasure.

This book list, supposedly from the BBC (but you know FaceBook...it could be from anywhere), includes lots of different literature for those with varied taste. Check out number one and number two on this list. It's not often Tolkien and Austen end up side by side, now, is it?

1. The Lord of the Rings, JRR Tolkien

2. Pride and Prejudice, Jane Austen

3. His Dark Materials, Philip Pullman

4. The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, Douglas Adams

5. Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, JK Rowling

6. To Kill a Mockingbird, Harper Lee

7. Winnie the Pooh, AA Milne

8. Nineteen Eighty-Four, George Orwell

9. The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, CS Lewis

10. Jane Eyre, Charlotte Brontë

11. Catch-22, Joseph Heller

12. Wuthering Heights, Emily Brontë

13. Birdsong, Sebastian Faulks

14. Rebecca, Daphne du Maurier

15. The Catcher in the Rye, JD Salinger

16. The Wind in the Willows, Kenneth Grahame

17. Great Expectations, Charles Dickens

18. Little Women, Louisa May Alcott

19. Captain Corelli's Mandolin, Louis de Bernieres

20. War and Peace, Leo Tolstoy

21. Gone with the Wind, Margaret Mitchell

22. Harry Potter And The Philosopher's Stone, JK Rowling

23. Harry Potter And The Chamber Of Secrets, JK Rowling

24. Harry Potter And The Prisoner Of Azkaban, JK Rowling

25. The Hobbit, JRR Tolkien

26. Tess Of The D'Urbervilles, Thomas Hardy

27. Middlemarch, George Eliot

28. A Prayer For Owen Meany, John Irving

29. The Grapes Of Wrath, John Steinbeck

30. Alice's Adventures In Wonderland, Lewis Carroll

31. The Story Of Tracy Beaker, Jacqueline Wilson

32. One Hundred Years Of Solitude, Gabriel García Márquez

33. The Pillars Of The Earth, Ken Follett

34. David Copperfield, Charles Dickens

35. Charlie And The Chocolate Factory, Roald Dahl

36. Treasure Island, Robert Louis Stevenson

37. A Town Like Alice, Nevil Shute

38. Persuasion, Jane Austen

39. Dune, Frank Herbert

40. Emma, Jane Austen

41. Anne Of Green Gables, LM Montgomery

42. Watership Down, Richard Adams

43. The Great Gatsby, F Scott Fitzgerald

44. The Count Of Monte Cristo, Alexandre Dumas

45. Brideshead Revisited, Evelyn Waugh

46. Animal Farm, George Orwell

47. A Christmas Carol, Charles Dickens

48. Far From The Madding Crowd, Thomas Hardy

49. Goodnight Mister Tom, Michelle Magorian

50. The Shell Seekers, Rosamunde Pilcher

51. The Secret Garden, Frances Hodgson Burnett

52. Of Mice And Men, John Steinbeck

53. The Stand, Stephen King

54. Anna Karenina, Leo Tolstoy

55. A Suitable Boy, Vikram Seth

56. The BFG, Roald Dahl

57. Swallows And Amazons, Arthur Ransome

58. Black Beauty, Anna Sewell

59. Artemis Fowl, Eoin Colfer

60. Crime And Punishment, Fyodor Dostoyevsky

61. Noughts And Crosses, Malorie Blackman

62. Memoirs Of A Geisha, Arthur Golden

63. A Tale Of Two Cities, Charles Dickens

64. The Thorn Birds, Colleen McCollough

65. Mort, Terry Pratchett

66. The Magic Faraway Tree, Enid Blyton

67. The Magus, John Fowles

68. Good Omens, Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman

69. Guards! Guards!, Terry Pratchett

70. Lord Of The Flies, William Golding

71. Perfume, Patrick Süskind

72. The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists, Robert Tressell

73. Night Watch, Terry Pratchett

74. Matilda, Roald Dahl

75. Bridget Jones's Diary, Helen Fielding

76. The Secret History, Donna Tartt

77. The Woman In White, Wilkie Collins

78. Ulysses, James Joyce

79. Bleak House, Charles Dickens

80. Double Act, Jacqueline Wilson

81. The Twits, Roald Dahl

82. I Capture The Castle, Dodie Smith

83. Holes, Louis Sachar

84. Gormenghast, Mervyn Peake

85. The God Of Small Things, Arundhati Roy

86. Vicky Angel, Jacqueline Wilson

87. Brave New World, Aldous Huxley

88. Cold Comfort Farm, Stella Gibbons

89. Magician, Raymond E Feist

90. On The Road, Jack Kerouac

91. The Godfather, Mario Puzo

92. The Clan Of The Cave Bear, Jean M Auel

93. The Colour Of Magic, Terry Pratchett

94. The Alchemist, Paulo Coelho

95. Katherine, Anya Seton

96. Kane And Abel, Jeffrey Archer

97. Love In The Time Of Cholera, Gabriel García Márquez

98. Girls In Love, Jacqueline Wilson

99. The Princess Diaries, Meg Cabot

100. Midnight's Children, Salman Rushdie

How many of these have you read? Which one is your favorite? Which ones might you like to read? Please do share!

Thursday, August 5, 2010

Working with Your Gifts

Zola’s words apply to life as well as art. Lately, I’ve been questioning what it means for people to embrace the art of life, to do the work with their gifts. Years ago, when I was beginning my faith journey at our current church, I had to call another member to invite her to join a committee. What I got in answer was an earful of dissatisfaction with the church, the pastor, and the lay leadership. When I asked the woman what other committees she was on and what else she did in the church, she replied with rhetorical circumlocutions that made it clear she did not do anything to make the church a better place. She was just showing up and then felt angry that church wasn’t what she wanted it to be.

That sort of passiveness doesn’t really make sense, yet we all fall victim to it at some point in our lives. We sit around holding onto our gift, waiting for someone else to do the work for us. We act as if the gift alone was precious and others ought to appreciate it without our having to lift a finger.

I once had a highly gifted friend whose graduate school advisors told him to write a dissertation on a topic that didn’t interest him but was in vogue at the time. My friend's response to this advice left me quite speechless. “Susan,” he said, “if those professors could just crawl in my head and see how brilliant I am, they wouldn’t ask me to write a dissertation in the first place.”

I had students with similar attitudes in my freshman composition classes. They blamed me for their own failure to make the grades they felt they deserved. One student, who was clearly gifted with language and wanted to be a writer, had no discipline to her writing and told me the rules I taught made her feel constrained. “I’m an excellent free-writer,” she said.

I replied, “Everyone is an excellent free-writer because the only audience for free-writing is you. When you have to communicate what’s going on in your head to someone else with written words, you have to shape your words to convey your meaning to your audience, not just to please yourself.” She said, “I don’t want to do that. I want to be free to express myself my own way.” From her perspective, the world owed it to her to interpret what she meant; she had no obligation to help anyone else understand her at all.

Sounds like a recipe for loneliness to me.

Now, let’s be clear that I’m not singling these two people out for scorn at all. I’m well aware when you point a finger at someone, there are three fingers pointing back at you. And like I said above, EVERYONE does this some time, in some way, and mostly, we’re totally blind to our own guilt. I’m so blind the only example I can think of from my own life is pretty benign in the grand scheme, but we can all very safely assume I’ve been just as arrogant as my friend and my student at some point—or many points—in my own life. And chances are, you have been, too.

During my first two years of college, I took 20th Century American Poetry and 20th Century British Poetry. I hated both classes. You see, my high-school education was rooted in classics through the Romantic Poets, with very little American poetry at all. I took both classes in college very passively, waiting for the professors to enlighten me as to the meaning of these weird (to me) poems that were not nearly as fun as Keats’ "Ode to a Nightingale" or Milton’s Paradise Lost or Homer’s Odyssey. I scorned the poetry and blamed the professors because they didn’t teach me anything. It was their fault.

See, I told you my example was benign. Or banal. Take your pick.

Anyway, by the time I got to graduate school, I’d figured out something about education—and life in general. You get out of it what you put into it. I’d put next to nothing into those two modern poetry classes in college, and now graduate school provided me with a second chance to learn—actively learn—about the poetry of William Carlos Williams, Siegfried Sassoon, Elizabeth Bishop, and Robert Lowell.

I took a poetry genre class with a mediocre professor, worked my butt off, learned a lot, but still didn’t have a good idea what these modern poets were trying to say.

I had one last chance: my comprehensive exam in poetry. At Wichita State, to get an MA in English, a student has to take three comprehensive exams: one on a genre, one on a literary period, and one on a major author. A student’s thesis determines what the content of each exam would be. My thesis was on Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, so my genre was poetry, my period was the Middle Ages, and my major author was, of course, Chaucer.

The mediocre professor wrote my poetry comp. Together, we had to agree on a book list that would be the basis for the exam. When he asked what I wanted to read, I confessed my utter ignorance and confusion with 20th century poetry and asked if he could recommend books to help me overcome it.

You should have seen how his face lit up. The books he recommended were horribly out of date by critical standards of the mid-1990s (this professor distrusted any criticism written after 1970), but they served me well. I now enjoy reading modern poetry because I put a lot into that exam and used the professor’s strengths in his outdated critical approach to outgrow my own intellectual weaknesses.

Two obvious lessons came out of this. First, standing on the sidelines waiting for someone else to enlighten me did not work; I had to let go of prejudice, get down and dirty, and work hard with a wide-open mind. You get more out of an experience if you put more into it, and sometimes it takes a lot more work than you thought it would. Generally, it's worth it in the end.

Second, confessing ignorance and asking for help are necessary to growth, not signs of weakness. I’d always thought Socrates was right when he said, “The more I know, the more I know that I know nothing.” After this, I knew he was right.

But there is a third lesson, tangential to these two, which is even more important. We’re all connected in life, and how we feel about that deeply influences how much we can grow together in community with others. My poetic enlightenment made me a much better teacher, for instance, better able to communicate my enthusiasm for literature in general with bored World Literature students. Also, my mediocre graduate professor doesn’t look so mediocre after all, does he?

In our church life, work life, and social life, the same lessons apply. When we jump in and give, really give, of our time and talents to others, amazing things can happen. We stop judging and start living. We feel connected and happy. One lovely example of this is my in-laws’ volunteering for Meals on Wheels. They don’t just deliver meals; they deliver a kind word and a smile, and they say they get more out of it than the people who get the food.

My mother, a dental hygienist, gave so much to her patients that when she retired, some of them cried, a few felt hurt and got mad at her for abandoning them, and many gave her gifts of gratitude and affection. Technically, all she did was clean their teeth, often hurting them in the process. But she did it with skill and kindness and caring, and her patients noticed.

Right now, I'm trying to decide whether or not to train as a Stephen Minister. It's a tough decision because on the one hand, the training will equip me to help other people in very direct ways, but I have doubts about my gifts for that sort of ministry. It might also take time away from writing. How do I choose where my gifts are needed most? Which gifts need more attention at this point in my life? Seems like a situation for lots of prayer and a few key conversations with people who know more than I to give me guidance.

How do you connect and grow in your life? Do you look for opportunities to grow? Are you doing the work that goes with your gifts? Where could you do better?

Friday, April 16, 2010

Words, Words, Words from Fannie R. Buchanan

The Surprise

This morning, plain as plain could be,

A little birdie called to me

"Come out! Come out! Come out and see!"

A butterfly all bright and gay

Went flitting on to show the way,

"Just follow me," it seemed to say.

And all around I heard the bees

Whispering something to the breeze.

I thought they whispered, "Apple trees."

And then I shouted with delight!

Someone had been there in the night

And turned the trees all pink and white!

From Book Trails: For Baby Feet

copyright 1928

Shepard and Lawrence, Inc.

Child Development, Inc.

Thursday, March 4, 2010

Choosing Books

If you’re a regular reader of this blog, you know I spend a substantial portion of my life at Barnes and Noble Booksellers breathing in the heady smell of paper and ink and glue. (And drinking mochas. With whip cream and caramel drizzle. But that’s a totally different essay.) I also volunteer a few hours a week at our sons' elementary school library. But I don’t have to go to Barnes and Noble or a library to be surrounded by books. Plenty of books live in almost every room of my house.

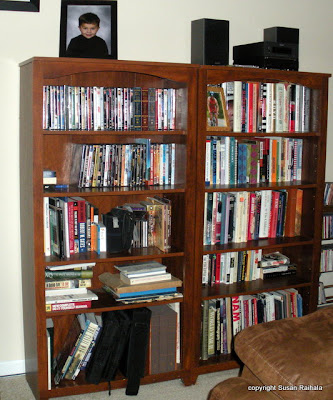

This is our Library. It’s supposed to be a sitting room/parlor/living room, but in our house, it’s the Library. The two book shelves on the left are mine, and the ones on the right belong to George. I’d love it if this room were decorated with real wood furniture rather than laminated particle board, but we spend too much money on books to afford nice bookshelves.

Wow, looking at this picture gives me so many ideas for other essays. I hadn’t noticed how many cool knick-knacks with interesting stories there are on these shelves. In more ways than one, these books are the backdrop of our lives.

These are the shelves to the right of the television in our family room. Most of these are George’s books, and the “grown-up” DVDs are shelved here, too.

These are to the left of the television. Obviously, the kids’ DVDs and some games are here, but the bottom three shelves are mostly my books.

Here’s the bookshelf beside my bed. It’s mostly novels and essays and a few devotionals. The stack of hard covers beside the bookshelf consists mostly of Anne Perry mysteries (a few signed by Perry herself), with some random stuff on top. The set of red books is a 1920s children’s series called Book Trails I read as a child. I love them.

George has a matching bookshelf full of military stuff, spy novels, and triathlon magazines as well as four shelves in the family room (not pictured) of cooking magazines and cook books. I don’t use those except under dire circumstances. We have more bookshelves in the basement, and of course the boys have their own bookshelves in their rooms.

Books make me happy. Their physical presence is a comfort I can carry with me anywhere…to the pool, into the tub, on a plane, to a waiting room. They keep me company, don't fuss when dog-eared, and wait patiently for me to pick them up when the spirit moves me.

So why the heck would I want a Kindle?

At the YMCA pool recently, a woman sat on a folding chair six feet from splashing children reading (if you can call it that) something on a Kindle. She kept putting the Kindle down, like she was embarrassed, or maybe bored. Then, a few minutes later she picked it up and read a bit more. Then, she put it down again. I started wondering what sort of book would cause a person to keep putting it down. Was she reading something boring, or uncomfortable, or naughty? I was hoping for naughty.

And then I realized the most important question in this situation was “What sort of person takes a $300 electronic gadget to read by a pool? Full of splashing children?” She’s a mom (her kids went to the same preschool as mine), so presumably she knows that children, water, and electronic gadgets should never, ever be within a quarter mile of each other.

And then I realized that I was spending way too much time paying attention to what this woman was doing. It really was none of my business.

Given my Luddite tendencies, I think Kindles and Nooks and other strangely-named electronic books are signs of the coming apocalypse. They, along with television screens in grocery store checkouts and medical waiting rooms and minivans, are reinforcing our screen culture. My son is buying into this and it scares me. He daily attempts to negotiate (or sneak) extra time on the Wii and wants a portable DS so he can look at a screen all the time no matter where he goes.

When I was his age, I looked at books all the time. I would eagerly open them, read, turn the page, read some more, and always regret the need for putting them down. My imagination sparked, my brain engaged, my heart soared and plummeted with the hero’s fortunes. I couldn’t wait to turn the page to see what happened next, but I wanted to make each page last as long as possible because it was so fun. That tension created a frisson of pleasure at the turn of each page that held me captive just as it has held curious and literate people captive since the first story was captured in ink.

More hip and tech-savvy people might ask how my walking around with my nose in a book was any different from Nick wanting to walk around with his nose buried in a DS. Clearly, these people need to read more books.

I already know all the arguments for electronic books and even admit that for certain situations (traveling, heavy college textbooks, people who don’t have space for large libraries like ours) they make sense.

I do, however, wonder how this will change people’s relationship with books. In particular, how will people choose books to read? In my experience, friends recommend books, favorite authors publish new books, reviewers on NPR praise books, and I stumble across books in books stores. These things prompt me to buy. I’ve never gone trolling online for books. I always looked at brick-and-mortar stores first, and then went online.

To illustrate this point, I pulled three random books off my bedside table and thought about what made me buy each. One thing all three purchases had in common is that I stumbled across them on shelves while browsing at Barnes and Noble with a mocha in my hand.

Animal, Vegetable, Miracle by Barbara Kingsolver. This one grabbed me because I liked Kingsolver’s novel Pigs in Heaven and also her essay about the Rock Bottom Remainders (a charity band that included Kingsolver, Dave Barry, Stephen King, Amy Tan, and others). I’d also read around in The Omnivore’s Dilemma (a book about where our food comes from), so the subject matter seemed interesting.

Why We Make Mistakes by Joseph T. Hallinan. There’s a deliberate typographical error on the happy orange cover that immediately grabbed my attention. (Well, I was a professional proofreader.) Then there’s the subtitle: “How We Look Without Seeing, Forget Things in Seconds, and Are All Pretty Sure We Are Way Above Average.” Could you resist exploring that one? But never, ever judge a book by its interesting cover. I’ve done that before and been wrong about the writing. (For instance, The Professor and the Madman by Simon Winchester. It takes dull prose to a whole new level.) I’d never heard of Hallinan before, so I picked up the book and read the introduction. Not only was the quality of the writing good, but his ideas were fascinating.

Never Have Your Dog Stuffed by Alan Alda. I grew up watching M*A*S*H, and after checking to make sure Alda could, indeed, write readable prose, I bought this one for a laugh and got much more. I reread it recently (the reason it was on my bedside table). This second reading was sparked by seeing the spine of the book on the bookshelf near my bed: a bit of serendipity that gives me joy.

Perhaps the process of downloading books to Kindles and Nooks and such will be as pleasurable as roaming shelves of a bookstore or library, but I doubt it. I do hope that people read more with the electronic book’s combination of screen appeal, compactness, and ease of book purchase. If people like looking at screens so much, perhaps it would be better to read a book than to play a mindless game. But will people make that choice? The lady at the YMCA pool sure seemed to be having a hard time getting into her book.

Certainly iPods have made it easier for people to listen to music, buy music, and carry music around with them. But I worry that too many books will languish unread in the memory chips of Kindles, which will break, get dropped, get wet, get stolen, and eventually grow obsolete.

I think I’d have a depressive breakdown if I lost all of Jane Austin in a freak pool accident. As it is now, if Pride and Prejudice gets soaked in my bubble bath, I’ll just run to Barnes and Noble, get a mocha, and search for another copy.

Who says you can’t buy happiness?

Friday, January 29, 2010

Juggling Books

I’m not funny. I just write that way. (Name that movie I’m paraphrasing!)

In real life, I am an unapologetic geek. I’m the weirdo in Bible study who pipes up with trivia tidbits like how as the bishops gained authority in the 8th and 9th centuries, they sapped the power of abbots and abbesses—especially the abbesses. Or how the popes saved the fish industry in Italy by declaring Fridays meat-free.

You know. That geek.

Anyway, in a past life, I was either a librarian at Alexandria (2nd century B.C.), a monk at Lindisfarne (7th century A.D.), a professor in Paris (14th century A.D.), or a Quaker rhetorician (19th century AD). Or perhaps I was all of the above. So it’s only logical that from the beginning of this life books have riveted my attention even when, perhaps, I should have been doing something else.

In school, books were my world. I knew that the secrets of life, the universe and everything lay hidden in them, and school provided the perfect excuse to juggle many books at one time. History, math, chemistry, biology, physics, novels, grammar handbooks, poetry, foreign languages…such diversity of subject matter challenged me to soak it all in, and I accepted the challenge joyfully.

This is why I know so much about classical, medieval, and Renaissance history despite the fact that most history classes are, generally speaking, mind-numbingly soporific. I can remember sitting in eighth grade history telling myself that surely there had to be something interesting about the Hittites; the text book just missed it. Maybe if I kept reading, I’d figure it out. No matter how boring the book, I shuffled through, made good grades, and never once understood why other kids had lost hope that the Hittites were anything but pointlessly boring dead people.

My faith in books stands unshaken, but my ability to multitask with them significantly declined when I had children. For the last ten years, I have rarely had two books going at once, unless, of course, I had already read them before. I reread books, having lunch with them as if they were old friends. It takes less mental energy to reread a book than it does to read it the first time, which is perfect for someone suffering from Mommy ADD.

I hoped when I started this blog that I would regain some of my powers of concentration and can happily report at least partial success. Right now, I am reading four different books, none of which I have read before. If you’re a fellow geek, you know just how cool that is.

Here they are, in case you’re curious.

The red leather-bound book is Volumes 1-2 of the 1950 edition of The Book of Knowledge, a children’s encyclopedia. Why, you might ask, is the 43-year-old geek reading an old children’s encyclopedia? To prove just how geeky I am, I guess. It’s an old book and smells of knights and Natives and oh!my!gosh! Geoffrey Chaucer! There’s a whole big entry on medieval literature, complete with anachronistic Victorian engravings and a fairy-tale retelling of Beowulf. It has articles as diverse as “The Wonder of the Train”; “The Artists of the Old Empires: Egypt, Babylonia, and Assyria”; “How to Renew the Edge of Your Screwdriver”; and “Birth, Life, and Death of a Plant.” It even has a poetry section with the following poem by Amy Lowell:

Sea Shell, Sea Shell,

Sing me a song, O please!

A song of ships, and sailor men,

And parrots, and tropical trees,

Of islands lost in the Spanish Main

Which no man ever may find again,

Of fishes and corals under the waves,

And sea-horses stabled in great green caves.

Sea Shell, Sea Shell,

Sing of the things you know so well.

Do kids today even know what the Spanish Main was? I’d like to go where it used to be because it’s a heck of a lot warmer and sunnier in the Spanish Main than Ohio in January.

The Way I See It by Temple Grandin contains mini-articles about autism. Grandin has a PhD in animal behavior and her own consulting firm that works to improve the conditions of animals raised for slaughter. She also has autism and writes with the authority of one who’s lived it. The Way I See It gives advice to parents and therapists on how to help their children with autism learn and mature to be useful contributors to society rather than warehoused and written-off disabled adults. I’ve always appreciated her unique point of view and find the tidbits of advice in this book quite useful.

Animal, Vegetable, Miracle tells the story of Barbara Kingsolver’s attempt to get closer to the food she eats. Another volume in the increasingly popular genre of do-something-weird-for-a-year-and-write-a-book-about-it, Animal, Vegetable, Miracle gives lots of interesting information about food: where it comes from, how it’s grown, how unnatural it is to eat asparagus in October. A bit preachy at times (I won’t stop eating asparagus in October), but an enlightening read nevertheless.

Finally, a volume of children’s literature caught my attention at Christmas so I bought it for Nick. The Percy Jackson series taps into my lifelong love affair with stories of the Greek and Roman gods. Unlike the Harry Potter series, these books are definitely for children, written in the first person from young Percy Jackson’s point of view. Percy has ADHD, dyslexia, and impulse-control issues. He’s also the half-blood son of Poseidon and a mortal woman who is tasked with saving the Olympian gods from total destruction. I wanted to read the book before seeing the movie, which comes out in February.

When I finish the Percy Jackson series, I’m going to dive into Ovid’s Metamorphoses. I read parts of this Roman classic in graduate school but never the whole thing. There’s something appealing about reading stories of transformation when I’m trying to transform myself. Of course, I’d rather not transform into a tree or have my liver plucked out daily by a giant eagle, but I’m sure you know what I mean.

It feels good to get back to normal (for me) with books. What is normal for you? Do you juggle multiple books or focus on one at a time? What are you reading right now? Chick lit? A book on raising designer chickens for fun and profit? The Bible? A how-to book on belly dancing? A children’s encyclopedia? Please share!

While you're thinking, I'll just go check the edges on my screwdrivers to see if they need tending. Who knew screwdriver edges were an encyclopedia-worthy topic? You learn something new every day....

Wednesday, January 13, 2010

Weekly Giggle #10

Impostor

Sometimes, the truth hurts. Sometimes, it's just funny.

Wednesday, December 9, 2009

Cutting Facets in the Gemstone of Life

“Like many culture debates, discussions over Positive Thinking have been hijacked by extremists, opportunists and professional depressives. People argue that you can get what you want by wanting it. Others that the world is a dark and evil place, and that should never be forgotten.”

Polarization by extremists is ubiquitous; we see it in politics and in breast feeding, in religion and in parenting, in education and in science. Extreme positions make me nervous. I’m happiest in the middle, sitting happily on the fence, enjoying a view of the big picture, yet vulnerable to attack from both sides. I’m the one trying to negotiate a compromise, find common ground, and shift perspective to a happier place where we can all get along. Naïve, yes, but that’s my interpretation of Positive Thinking.

Like Katz, I don’t think you can get what you want by wanting it, and people who deny there’s anything wrong in the world are lazy and saving themselves the bother of making the world a better place. But those who focus only on the bad, on how everything is going down the tubes, on how the End is near, drive me batty, too. They are whiners who are also lazy and saving themselves the bother of making the world a better place. What’s the point, after all?

Opportunists take advantage of these polar impulses of humanity. Self-help authors and talking heads strike the mother lode when they get Oprah-fied, and mass media freaks people out in an effort to win audience share. Technology means we are bombarded with these polarized messages constantly.

A few years ago, I came across a quotation from Elizabeth Bowen that struck me as profoundly true:

“If you look at life one way, there is always cause for alarm.”

I encountered a lot of “professional depressives” in academia, where hyper-specialization dangerously narrows people’s perspectives on the world. An English professor at Duke, Dr. J, once told me I could NOT double major in chemistry and English because the two subjects had nothing in common. I made sure never, ever to take a class with him. Professor J’s perspective was sadly limited, like the palette of a man who will only eat sour food. More than two decades later, my fascination with science remains strong, even if I didn’t make a career of it. I find a lot of philosophical common ground between science and English these days, and both have made it easier for me to cope with being the mother of an autistic child.

One of my graduate school professors, Dr. H, felt that any literary theory other than the one he preached was not only misguided but terribly wrong, and he graded students accordingly. His class was not a place for intellectual growth and open exchange of ideas.

But another of my graduate professors did promote intellectual growth and open exchange of ideas. Dr. Nancy West, a Victorian literature scholar with a strong interest in media studies, once shared a simile with me. A piece of literature, she said, is like a gemstone; each different literary theory cuts just one facet, but what really makes a gemstone sparkle is lots of facets. A piece of literature means more, sparkles more, when it's looked at from multiple perspectives.

Isn’t that a wonderful image for life? When we consciously look at life from lots of points of view, we see it better, it sparkles more, and it is much more vibrant and interesting.

Consider this thought experiment. First, imagine the feeling of standing in a mountain meadow with land rising up above you and falling down below you. Are you there? Can you feel the sun, hear the insects and pikas and birds? Can you smell the wildflowers and grass and the spongy moss under your hiking boots? Can you feel the cool mountain breeze ruffle your hair?

Next, erase the mountain scene from your mental eye and imagine standing on a beach with a sand dune behind you and the whole wide ocean in front of you. Can you feel the sand between your toes and the warm breeze whipping your hair and salt spray sticking to your skin? Can you hear the seagulls and the waves, and see the skittering of crabs and fountains of water shot up from the sand by mollusks? Can you smell the salt and sea wrack?

Now, can you tell me which view is right?

You may have a preference, of course, and be drawn to one more than the other, but both of these views are part of the gemstone of the world. Is one right? No.

I only know Jon Katz through his blog, which means my acquaintance with him is seriously limited, but I think he’s sitting near me on that fence in the middle. When I wrote him an email to express my appreciation for his blog and to share Dr. West’s gemstone simile, I did not expect a response. Katz is a published author with a huge blog readership. On his blog's contact page, he clearly states he cannot read, much less respond, to all the messages he receives. To my delighted surprise, however, he graciously replied to my email.

Our brief email exchange isn’t the sort of scintillating philosophical discourse others would pay money to read, but it was very satisfying nevertheless. If the Internet is good for nothing else, it allows people to connect briefly, find common ground, and move on in the certain knowledge that they are not entirely alone. Katz’s life has been very different from mine, and he’s in a completely different stage of life. But we’re both thinking along the same lines.

I’ve also gathered a new tidbit in my growing collection of evidence to support my belief that fence-sitting is a healthy place to be because the view is divine. In his reply, Katz wrote:

“I think academics have the same problem journalists and many writers do. They only talk to each other. One thing I love about where I live is I can't get away with that. I have to talk to farmers and sheriffs and pastors and unemployed highway workers and that keeps me a bit in perspective, I think. I think of the world as a collection of tents, and I am not welcome in most of them, which turns out to be precisely where I belong.”

Too often, we get mired in our own narrow point of view, stuck in our own tent. Our perspective gets distorted by that narrowness, and we have to work hard to open it up, look around, and realize that everyone isn’t seeing the world the exact same way.

In the process, ironically, we realize that we’re not all so different either.

Monday, August 3, 2009

Gratitude Journal #8

What are you grateful for today?

Edited: Turns out Caedmon didn't write Elene at all. It was written by the Anglo-Saxon poet Cynewulf, about whom very little is known. Sorry for the error above!

Friday, July 17, 2009

Words, Words, Words from Mary Oliver

If you feel so inclined, click the link, read the poem, and come back to the comments here to share your impression of Oliver's words.

The Place I Want to Get Back to

by Mary Oliver

What comes to my mind when I think of the peaceful connectedness of Oliver's poem is feeling my babies move inside me. I don't literally want to go back to that place (yikes!), but the memory of my babies moving definitely takes me to that house called Gratitude.

Friday, July 10, 2009

Words, Words, Words...and a Give-Away

Last night, Nick and I found this poetic gem in an old, old book he pulled off a shelf next to my bed. It’s one in a series of books for children published in the 1920s called Book Trails. Each volume is an anthology with stories, fables, poems, and lovely illustrations centered on a particular theme. These battered, yellowing volumes exude the nostalgic scent of eau de Carnegie Library (my favorite perfume) and contain random scribblings in crayon and pencil by my mother and aunt and perhaps even my own young self. Nick was enchanted with these books, and amazed that they once enchanted his grandmother, too.

Lost!

I lost my big Geography

As I came home today.

I laid it down, I—can’t—think—where—

I stopped a bit to play.

It was a nice Geography,

The seas were colored in blue;

And there were bright green valleys

With rivers running through.

Australia’s there and Europe too,

And big old Africa;

But best and biggest map of all

Was our America.

And now my shoestring’s in a knot,

My hair is all uncurled;

I only played ten minutes but—

I’ve lost the whole big world!

Helen Coale Crew

Ms. Crew may not have had Shakespeare’s gift for words, words, words, but she captures the challenges and frustrations and perspective of childhood delightfully, don’t you think? I sure felt like I had lost the whole big world a few times!

Now for the give-away.

Share the title of a fondly remembered children’s book or poem from your own childhood in the comments for a random chance to win a $20 (US) gift card to Barnes and Noble. (If you live outside the United States and win, I will send you an electronic gift card for use at B&N dot com.)

For those who usually read the blog in their email, click on the link to the blog directly, scroll to the bottom of this post, and click Comment to enter.

Contest ends at 12:00 Sunday night, July 12, 2009. One entry per person, please.

Tuesday, June 23, 2009

Fiction over Fact

We discussed approaches to teaching history (well, I asked questions and Tom gave very thorough, interesting answers). In academic studies, as in the fashion industry, various trends come and go, and I wanted to know what was currently in vogue.

This wasn’t idle curiosity on my part. My thesis entertained a somewhat New Historical approach to Chaucer’s Wife of Bath, and I own scores of medieval history books. I adore history—at least as far as it is useful for illuminating literature. I know, for instance, a surprising amount about battle tactics of knights and the invention of the long bow, and I therefore know why the English kicked French butt at the battle of Crécy in 1346, but only because I wrote a paper on Chaucer’s “Squire’s Tale” and needed that information to support my argument about the pointlessness of the knightly class in late 14th century literature.

Hello? Tap. Tap. Are you still with me? I’m sorry. I know most people don’t really care about the pointlessness of the knightly class in late 14th century literature. Please accept my apologies for bringing it up.

My talk with Tom reminded me of an NPR report about how men generally read more nonfiction and women generally read more fiction and poetry. No definitive answer has been found to explain this difference so I started a little research of my own and asked Tom why he generally prefers nonfiction. He answered, stroking his chin professorially, “Fiction is an inefficient means of communicating information, and I decided it was a waste of my time reading it.” Hmmm. Data point number one.

I then asked my husband, George, the same question. He answered, “You know, when I read, I want information, and it’s just easier for me to get what I want reading nonfiction.” Data point number two.

Two test subjects may not constitute a valid study, but I’m certain most women will agree with the immediate conclusion I drew from my data, which is this: men are infinitely weird.

Let’s examine the weirdness, shall we? The charge that “fiction is an inefficient means of communicating information,” as Tom states, requires very narrow definitions of “information” and “efficient.” The images, symbols, allusions, metaphors, and general rhetorical richness of fiction and poetry communicate rather a lot of information in very few words, don’t you think? For example, let us consider the following short poem by William Carlos Williams:

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chickens.

What a great little poem. Despite its brevity, there is A LOT going on in it. I gave a five-minute oral presentation on it in 1982. By the end of college in December, 1987, I could have written a 20-page paper on it, easily. By the end of graduate school in 1994, I could have written a book-length dissertation on just these four lines.

How is this possible?

Williams efficiently crams an enormous amount of information (only we literary scholars call it “meaning”) into the image he creates with these 16 simple, ordinary words. The poem speaks to all sorts of universal concepts, including one that drives our Word of the Year project to start anew, fresh and clean. It speaks to the sacrificial properties of blood; of baptismal waters that renew and purify; of the redeeming power of the simplest, most ordinary things (like wheel barrows and chickens); of the value of honest manual labor; and of my favorite subject, perspective.

Okay, I may have lost you at “sacrificial properties of blood” but my point here is that just a few words can convey huge amounts of information if you know what information to look for. Reading literature well requires two things: knowing the specialized vocabulary of literary study and reading lots of literature. The more you study and read, the bigger your frame of reference and the more efficiently you can extract the information encoded in it.

The fact that this sort of information bears no relevance to the economic rise and environmental impact of automobiles is hardly the fault of the poem, but it does explain why such material is a waste of time for an economic/environmental historian like Tom. It also explains George’s statement that it’s easier to get information out of nonfiction: nonfiction doesn’t employ dense literary language but tends to lay out an argument or story in clearly logical fashion.

But does this make much difference in the process of reading nonfiction well? I don’t think so.

Let’s take a book off George’s shelf to illustrate my point. You don’t have to read a bunch of books about the atomic bomb to follow the argument in The Making of the Atomic Bomb. You can easily extract a lot of information about the bomb in the process. But what can you DO with that information? You would still have to read a bunch of other books about the atomic bomb to evaluate The Making of the Atomic Bomb critically for its meaning and to find the holes in its argument and the weak spots in its evidence.

So there’s not a big difference between reading fiction or nonfiction well…both require reading a lot to understand nuances and the deeper significance of the subject matter. The biggest difference is content. In fiction, the content is created to explore philosophical questions about life for which there are no easy answers: why are we here, how do we find ourselves in particular situations, what makes us who we are, what is love? Fiction gives us lots of information to explore these sorts of questions. It’s also written to entertain, which makes it more fun than nonfiction about the atomic bomb, don’t you think?

If, however, you’re interested in questions like how was the atomic bomb built, what were the motives behind its construction, who was involved, how did they feel about it, and what happened as a result, then nonfiction is definitely more helpful—and if it’s well written, it can be entertaining, too.

Ultimately, “information” is really just whatever interests the reader. Most women I know are content with just a little information on the atomic bomb and automobiles but are endlessly fascinated by relationships and love and human behavior.

Whenever I was forced to read “information” on economic history (John Stuart Mill comes immediately—and painfully—to mind), my brain would get all slippery and distractible. The buzz of my tinnitus, which was easy enough to ignore when I read Shakespeare or the Brontë sisters or James Joyce, would amplify annoyingly under the influence of Mill, and I’d start formulating grocery lists in my head or daydreaming about eating a Ruby Tuesday’s Chocolate Tall Cake all by myself. Yummy.

After a while, I would realize my brain wasn’t taking in a single bit of information from the page. I would tell myself, “Focus, Susan! FOCUS! You’re going to be tested on this crap!” To this day, I can’t tell you what Mill’s argument was. My brain never could adequately absorb it.

Is this what it’s like for guys when they have to read A Midsummer Night’s Dream or Wuthering Heights?

My bookshelves contain nonfiction on subjects other than medieval history, such as paper crafts, science, the human brain, autism, and special education. I don’t read fiction for information on those subjects (although there is a fun mystery series about scrapbooking), so I can understand Tom and George’s reasons for preferring nonfiction for their own areas of interest. I cannot, however, understand Tom’s view of fiction as a waste of his time in general or George’s inability to finish the second Thursday Next novel by Jasper Fforde because it’s totally brilliant satire at its postmodern silliest.

Men and women are different. (Am I not the Master of the Obvious?) I’m convinced that testosterone and estrogen have a greater impact on our brains than anyone outside the specialized field of endocrinology has yet realized. No matter how many federal dollars are spent researching the psychology of gender-based reading preferences, women are generally going to buy more fiction and poetry, and men are generally going to buy more nonfiction. We are chemically motivated to be interested in different things, and really, what’s wrong with that?

I’ll end this far too meandering essay with a quick confession…every time I read the wheel barrow poem by Williams aloud, I have to work really hard not to laugh when I get to the white chickens. Chickens have that effect on me. Read Chaucer’s “Nun’s Priest’s Tale” and you’ll have all the information you need to understand why.

Note: I will not have connectivity until Monday, June 29, and will be unable to reply to your emails or comments until then. But, as always, your comments and responses are very much appreciated!

Thursday, October 9, 2008

"What Should I Read?"

Sigh.

Unfortunately, normal people should be nervous about asking people with advanced degrees what to read, because people with advanced degrees are almost always mentally unbalanced. They often specialize in subjects that most people don’t care a fig about, and by “specialize,” I really mean “obsess.” If your obsession leads you to a career as something useful like a neurosurgeon, people respect you for it because you can save lives and make good money doing it. But what if your obsession doesn’t pay well and never saved a life? What if most people think it is a total waste of your time, effort, and energy?

Welcome to my world. I’m obsessed with almost anything written in the Middle Ages (c. 410-1475). I have a huge bookshelf full of medieval literature. This makes me very happy, but normal people usually avoid medieval literature unless forced to read it by a teacher who, they are convinced, wants them to suffer.

It’s lonely being me sometimes.

How did medieval literature become my obsession? I wanted to be a sophisticated reader and knew that sophisticated readers read books written by dead people like Shakespeare and Homer and Hemingway. That’s what schools teach you in 9th grade, which was when I decided my reading should become sophisticated. I was a budding intellectual snob, and my English teachers encouraged me shamelessly. Furthermore, I was a goody-two-shoes who did my homework without being asked, kept a dime between my knees on the rare occasions I had dates, and always told the truth. Just call me Sandra Dee. All that repression was bound to come out somehow.

In eleventh grade, it happened. I discovered that sophisticated literature could be naughty. We read The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer. My favorite was "The Miller’s Tale," a bawdy story about adultery and very literal ass-kissing that actually makes pubic hair the punchline of a joke. I quickly decided I wanted to be a medievalist so I could read more naughty literature and feel sophisticated while doing it. So to speak. This is how we goody-two-shoes rebel; we become geeks.

In college, I majored in English and Medieval and Renaissance Studies. The Renaissance was certainly fun—it had Shakespeare and Queen Elizabeth the First and Leonardo da Vinci, after all. But for true rollicking bawdiness and sheer strangeness, you can’t beat the Middle Ages. This was the age of faith and the heyday of the Catholic Church. The Middle Ages had the Inquisition, philosophical debates over how many angels fit on the head of a pin, and trial by ordeal (where God settled your guilt or innocence in bizarrely sadistic ways). All that religion ironically highlighted the earthier aspects of human existence. I soaked it all in—the good, the bad, and the just plain weird—like an alcoholic on a bender and kept looking for more.

While doing research for a very serious medieval history class my sophomore year, I stumbled across a book on the Bayeux Tapestry, an embroidery done in the eleventh century to illustrate William the Bastard’s conquest of England in 1066. It was almost certainly commissioned by Bishop Odo and hung in his cathedral at Bayeux for hundreds of years. In the lower margin of the embroidery, which measures an impressive 20 inches tall by 230 feet long, there is a little vignette which shows a naked man with a huge, um, part reaching out to a naked woman. Honestly, what is not to love about this fabulously graphic juxtaposition of headless, blood-dripping corpses and laughably comic lust? It's just so...medieval.

In graduate school, amidst my more serious papers on Beowulf, Quaker rhetoric, and feminism, I gave a very entertaining presentation on a piece of medieval pornography called The Romance of the Rose, a French poem about a lover who spends a lot of time figuring out how to pluck a woman named Rose. The presentation was a hit with my professor and fellow grad students, especially because I included medieval illustrations of the lover plucking his Rose in a canopied bed.

Like all normal, healthy people, English professors and graduate students are obsessed with sex; we’re human and hardwired for it by Mother Nature. Unlike normal, healthy people, however, English professors and graduate students dress up their interest in highly opaque jargon and tweed jackets. Sex is much more sophisticated and intellectual when it is dressed up this way.

We tweedy geeks instantly fall in love with almost any piece of literature that has been banned anywhere for any reason. Lots of medieval literature has been banned. I wrote my thesis on Chaucer’s Wife of Bath, a frequent victim of banning even though she’s only a little bit bawdy. Mainly, she threatens uptight religious fundamentalists’ ideas about how women are the root cause of all evil and need to be kept in their place by men. Even Chaucer couldn’t keep the Wife of Bath in her place, and he wrote her. She takes on a vigorously independent life of her own and is openly contemptuous of men’s feeble attempts to control her. She’s a blast.

I could have written my thesis on something more spiritual, like the morality play Everyman. Trust me: no one, not even fundamentalists with book-burning tendencies, would ban Everyman. It’s a complete buzz kill—beautiful, yes, but definitely a buzz kill. The Wife of Bath joins the Canterbury pilgrims on her quest for a sixth husband just so she can be the boss of him and keep him in his proper place, which is in her bed. Doesn’t that sound more interesting than a play in which Everyman says goodbye to Worldly Goods and his five Wits because only Good Deeds will go with him to the grave? I certainly thought so, and because I discussed the Wife of Bath with appropriately serious jargon and proper footnotes, so did every single member of my thesis committee.

Which leads me back to my original point, from which I have badly strayed. If you were to ask me what you should read, my answer might surprise you.

It’s this. Read whatever you want.

That’s what I do. I read great literature of both the bawdy kind and not-bawdy kind because I’m mental unbalanced, but I also read historical fiction, murder mysteries, science fiction, chick lit, and Harry Potter with equal enthusiasm. You’ll even find a variety of nonfiction on my overflowing bookshelves. Technically, I am a “master” reader who could work a room at a Modern Language Association Conference if I had to, but what sophisticated reading taught me is that reading should be…fun.

Right now my mother is thanking the scholarship and financial aid gods that she didn’t pay much for my very expensive college education.

I will leave you with a few wise words from an exceedingly sophisticated source. Professor Lee Patterson, a top-notch medievalist, once asked his class, “Why do we read literature?” When someone offered up the standard answer (“Because it makes us better people”), he said, “I know plenty of people who’ve read great books their whole lives, and some of them are real assholes. The honest reason we read these books is because they are fun.”

Amen, Brother Patterson. Amen.

Thursday, September 4, 2008

Forgive Me, Father, for I Have Sinned

Oh, thank you!

My list of literary sins is long. If you need a potty break, Father, I’ll understand.

I confess that I have hated some of the Great Books of Western Civilization.

I know. It’s shocking, isn’t it? I do have a master’s degree in literature, after all. I ought to love these Great Books, ought to talk about them with reverence, and ought to honor them for their brilliance. But my heart just isn’t in these:

--The Aeneid, by Virgil (Homer, even if he never really lived, was a much better storyteller. Those Romans just couldn’t do Greek as well as the Greeks did. I loved Virgil in Dante’s Inferno, though.)

--The Song of Roland (Honestly, Father, it’s the only work of literature from the Middle Ages that I just can’t make myself like. Maybe I need to read it again. That worked with Beowulf….)

--Don Juan, by George Gordon, Lord Byron (He single-handedly killed Romanticism. Okay, not really, but oh, my poor brain.)

--In Memoriam, by Alfred, Lord Tennyson (Um, maybe Alfred killed Romanticism. I’m sorry for his loss, but any “Book” that makes me pinch my cheeks to stay awake is evil, no matter how “Great” it is.)

--David Copperfield, by Charles Dickens (Yes, yes, I loved Bleak House, Hard Times, A Christmas Carol, and Great Expectations, but why is DC so very, very long?)

--The Story of an African Farm, by Olive Schreiner (Olive was a woman writer, and I am a woman—sort of a feminist, even—and should honor her for publishing a serious book in a man’s world, but I just can’t. I can’t!)

--A Doll’s House, by Henrik Ibsen (I read it, honestly, but don’t even remember enough to make a pithy comment. Is that bad?)

--Anything and everything written by Thomas Hardy: prose, poetry, all of it … even the few pieces he wrote that I haven’t been forced to read. I really tried with Tess but just couldn’t bring myself to care anything about her. What is wrong with me, Father?

--The Red Badge of Courage, by Stephen Crane (This is a ninth-grade torture device, right?)

--A Passage to India, by E.M. Forster (Teachers must use this as punishment for all the naughty thoughts eleventh graders have. It doesn’t help.)

--The Old Man and the Sea, by Ernest Hemingway (Yeah, yeah, I get that Papa was a great writer and his style was revolutionary, but I just can’t care because his “revolutionary” style is so freaking depressing. And truly, the fish gets eaten by sharks. Shouldn’t the old man be grateful HE wasn’t eaten? Let’s get our priorities straight, shall we?)

--The Pearl, by John Steinbeck (At least it’s short.)

Then there are the Great Books I tried to read but just couldn’t slog through no matter how hard I worked at it. They weren’t even assigned, but I felt like I “should” read them. Oh, how very silly of me:

--William Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom (I love long sentences. Usually.)

--Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita (I almost finished. Does that count?)

--John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath (Does the turtle ever get across the road? Never mind. I just don’t care.)

--Albert Camus’ The Plague (I only read two paragraphs, but it sat on my bookshelf for several years before going to the used book store. What’s that you say, Father? The road to hell is paved with good intentions?)

--Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (Excuse me, Father, but do you have to be on drugs to get Jack’s point with this one?)

There’s also the one assigned book that I didn’t read at all, though I wrote a reasonably competent paper on it with the help of the venerable Professor Cliff Notes in tenth grade:

Babbitt, by Sinclair Lewis

Finally, Father, there are many classics I never read, yet I call myself well-read. Does this make me a poser? This list could go on forever, especially where American novels and poetry are concerned. Do you think I’ve made up for those Great Books that I haven’t read by reading a lot of really obscure—but definitely Great—medieval literature? After all, the medieval period was the Age of Faith. That should count for something.

I’m certain that there are other literary sins I am neglecting to confess, but frankly, I’ve blocked them from my memory.

No, Father, I don’t sound very contrite, do I? Must I be contrite for forgiveness? Can’t I just pay a pardoner and be absolved? Oh, pardoners don’t exist anymore? What a shame. Perhaps I can take H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine back to the Middle Ages and pay a visit to Chaucer’s Pardoner. Does the machine make a stop in the Middle Ages? I can’t remember.

What did you say? You mean there’s no such thing as a literary sin? It’s not a sin to dislike Great Books? I won’t burn in Hell? I don’t have to turn in my library card? I’m not a cultural infidel?

Oh, what a relief!

Saturday, July 26, 2008

A Daring Adventure

Ask most 40-somethings to recall the subject of their high school graduation speech and most will say, “Huh?” They were way too busy sneaking sips from flasks to pay attention to some old duffer talk about the importance of this moment, a new beginning, opportunity unlimited, yadda, yadda.

I, however, remember my high school graduation speech quite clearly because I am a geek and because that man whose name I don’t remember said something I needed to hear. It resonated in my soul, this thing I already “knew” but had never thought relevant to myself. So I listened.

And I was a geek. Did I mention that?

Nameless Graduation Speaker began his speech with a reading from The Hobbit. A little background on my relationship with the venerable J. R. R. Tolkien is in order here. My long obsession with The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings began in seventh grade. When I was a senior, my mother walked into my room and picked up my dog-eared copy of The Fellowship of the Ring. She read a random line from a random page. I promptly told her she was reading from the chapter titled “The Council of Elrond” and that Boromir was speaking, and then I quoted the poem below that bit of dialogue in its entirety. Mom threw the book on the bed in disgust and walked out. I smirked in a very self-satisfied sort of way, and there the memory ends.

Yes, I was a geek.

So when Nameless Graduation Speaker launched in on The Hobbit, he captured my complete attention. For those who haven’t read it, the first chapter of The Hobbit takes our unlikely hero, the fat, comfortable, complaisant Bilbo Baggins of Bag End, and whisks him away on an adventure—nasty, dangerous, uncomfortable—that changes Bilbo and the history of his world forever.

Now, I knew I was heading off on an adventure, going to college and away from home. Unlike Bilbo, I wanted my adventure and never thought there might be anything nasty or uncomfortable about it. After all, I HAD A PLAN. I was heading off to Duke University to major in chemistry, then off to graduate school for a PhD. Bilbo forgot his hat. I wouldn’t forget anything. I had lists.

But Nameless Graduation Speaker’s point was this: we may think, like Bilbo, that we have our futures all worked out, planned to the least detail. In reality, it is the unexpected, unplanned adventures we need to be open to, or we may miss our chance to make a difference and maybe even become a hero.

Wow.

Perhaps it was this speech that made me so willing to modify my plan. Or maybe I just woke up one morning and realized my plan was stupid. Or I was too stupid for the plan. Whatever. Six months after hearing this speech, I ditched the chemistry major, declared for English, and never looked back. That bold little move has changed my life and taught me more than I could ever have anticipated. For instance,

1. I can speak in public without dying or even passing out.

2. If I can write intelligently about Milton’s “L’Allegro” and “Il Penseroso,” I can also write respectable copy about rebates on Ford pick-ups and successfully edit a white paper on synchronous dynamic random access memory (without understanding a word of it).

3. Best of all, skills used when reading Beowulf or Derrida or the sonnets of John Donne will also help a person identify urban myth emails without checking Snopes and navigate the murky waters of autism treatment literature.

Valuable life lessons, indeed.

Pursuing English was a choice, but since then, many unexpected adventures—sometimes nasty and uncomfortable—have swept me away. Like Bilbo, there were times when I wanted to run back to my hobbit hole and let the trolls get on with roasting or boiling the dwarves as they saw fit. Going out your front door can be a dangerous business sometimes, and whether I’ll turn out to be anyone’s hero in the end is questionable. I’ve never to my knowledge saved a life, found a magic ring, or played riddles with a creepy little monster. I’ve certainly never stolen the Arkenstone and brought peace to the land.

My adventures have been more . . . real. I married the United States Air Force and served my country as a “dependent spouse” for 20 years, which included such exciting duties as being designated driver to drunken Air Force aviators every Friday night for two years in Wichita, Kansas. I taught reluctant and occasionally hostile college students that you may indeed start a sentence with “and” or “but,” but generally not with “however.” I moved nine times in twenty years, saw my husband off to two wars, grew two aliens in my womb, and went from working woman to stay-at-home mom—my biggest and most unexpected adventure yet.

Hellen Keller wrote, “Life is a daring adventure or nothing.” I love this, especially when you consider that anything can be a “daring adventure.” You don’t have to sneak your dwarf friends away from a bunch of drunken wood elves to have a daring adventure. (Now that I think of it, though, I sort of had that adventure in Wichita....) If you’ve never thought of grocery shopping as a daring adventure, then let me loan you my two boys. You’ll get my drift before you finish picking out the lettuce. Daring adventure, indeed.

So thank you, Nameless Graduation Speaker, for showing me that the stories I love are relevant to me and to my life, and for giving me permission to abandon my plan and to be whisked away on my own daring adventure. I heard you.